St Hubert Revamped

Republished from the June 1949 issue of the Roundel

by F/O W. M. Lee and F/O M. A. East

Introduction

The rarid growth of Canada’s fighter defence programme at RCAF Station, St. Hubert, P.Q. may be aptly described by the phrase recently coined for the RCAF’s Silver Jubilee: “SO MUCH IN SO SHORT A TIME.” In less than three years, St. Hubert has risen from a retired wartime flying station to an organization embracing Caneda’s first post-war regular fighter squadron, an operational training unit, two auxiliary fighter squadrons, and a radar and communications unit. In addition, members of the RCAF’s second fighter squadron are presently receiving operational training at the O.T.U.—although the squadron itself has not yet been formed.

Designed originally as a mooring-base for trans-Atlantic dirigible service, St. Hubert was quickly converted into a Service Flying Training School early in the last war. The station contributed over 1,000 pilots to the stream of air-crew trained by the B.C.A.T.P. Towards the close of the war, the S.F.T.S. was transferred to the west, and St. Hubert temporarily passed out of the spotlight.

During October, 1946, two Montreal auxiliary fighter squadrons were formed, and week-ends at St. Hubert began to echo again with the bustle of earlier days. Since then, with the addition of new units, the Station’s stature in Canada’s air defence has increased immeasurably.

The O.T.U.

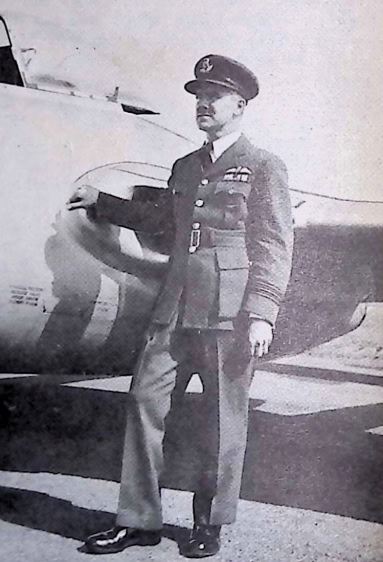

The Operational Training Unit, where wartime pilots and former Flight Cadets are converted to Vampires, occupies a prominent position in the RCAF’s peacetime flying programme. Commanded by Wing Cdr. “Bud” Malloy, D.F.C., well-known fighter pilot and flying instructor in the last war, the O.T.U. is looking forward to turning out its first batch of fully qualified jet fighter pilots in the very near future. The 12-week course, the first seven weeks of which are occupied half with ground and half with air training, includes instruction in low and high altitude flying, navigation, aerial interception, formation flying, and armament practice.

With dual instruction an impossibility in the single-seat Vampire, students receive thorough ground training before they ever step into a cockpit. A stiff ground examination, requiring 85% for a pass (average mark for the first course was over 96%), and close to 30 hours in Harvards, Prepare the pilots for the experience of flying the 500-mile-per-hour Vamps.

Wing Cdr. Malloy has a top-notch trio of experienced jet pilots in Fit. Lt. ‘Joe’ Edwards, Fit. Lt. “Irish” Ireland, D.F.C., and F /O Freddie Evans, D.F.C., to instruct the former Flight Cadets, whose average age is 20. Although susceptibility to blackout is to a large degree dependent upon physical condition, the student pilots are not restricted in any way after working hours. Says Freddie Evans: “They are conscious of the fact that they are flying high-speed aircraft, and they govern themselves accordingly.”

The O.T.U. teaches a brand of formation flying that leaves the ground-watcher breathless. The main formation, called the “Fluid Six,” consists of two staggered lead fighters trailed in a “V” by two more pairs of staggered aircraft. Although the formation is basically simple, it can carry out numerous intricate manoeuvres. Jet-propelled aircraft are tricky to handle in formation work at first, because of the tendency to lag. With a conventional fighter, a touch of the throttle is almost immediately followed by acceleration of the aircraft. The jet engine, however, does not react so swiftly. The pilot must learn to take this fact into consideration when manoeuvring his plane at close quarters with other aircraft. Flt. Lt. Edwards makes veiled reference to another formation the school intends to try out. It is picturesquely titled ‘The Finger Four.” But that is for the future…

The school is trying to develop a Canadian brand of fighter tactics—based, naturally enough, on the wider experience of the RAF, the USAF, and the USN.

The pilots themselves are fond of the Vampire. They have found it to be a reliable aircraft that demands only common-sense handling. As one of them puts it: “One of the big dangers in flying jets is the possibility of being injured in an automobile crash on the long drive out to the flying field.” .

The young students get ample opportunity for practice. Interceptor runs against Lancasters are an important phase of the course. Using Battle-of-Britain technique, the flyers are alerted to their machines, and controlled in their attack by ground radar systems. The Lanc. crews try every type of manoeuvre to get in a simulated bombing run over the station, while the radar controllers peer at their screens for an indication that an attack is on. When word is flashed to the ready-room, the pilots rush to their aircraft, take off in formations, and climb to height, all the time following the instructions of the ground controller. Substantially, this is exactly what would happen in reality.

Typical of the young men receiving this training is F/O Claude LaFrance, 19, of Quebec City, who entered the Air Force in September, 1947. Trained as a pilot at Centralia, he finds that flying a Vampire is an experience that makes life worth living.

It takes a highly trained corps of mechanics (aero-engine, airframe, and instrument), electricians, armourers, and others, to keep the aircraft in the air. St. Hubert has them all. F/Sgt. J. S. Brock, a former RAF pilot who served on operations overseas as a Flight Lieutenant, has nothing but praise for the veteran and not-so-veteran tradesmen under his command.

Predominantly high in trade grouping (average minimum: Group 3 outright), his men have a mature idea of their position in the overall defence scheme of the Air Force. What F /Sgt. Brock likes about the new ones among them is the enthusiasm with which they tackle their jobs. He says: ‘Most of them would never admit it, but they actually get a big kick out of seeing the results of their work flying about the Montreal skies.’’ Although the armourers grumble a bit at having to lie down in order to reload the four 20-millimeter canons in the nose, tradesmen generally have a sincere affection for the slick little Vampire, which they call the “Screaming Minny” — because, as LAC “Chuck” Empy puts it, “it sounds like a thousand blowtorches all going at once.” The nickname “Minny,” incidentally, stems from the “Minenwerfers’’— the German mortars of World War I. Some of the more experienced mechanics say they can judge the condition of a jet-engine by its scream.

Probably the person on the station who believes he knows the jet-plane best is a big good-natured fellow named “Sub,” a black-coated Labrador retriever belonging to one of the pilots. He used to romp about the hangars and tarmac on a daily inspection tour. One day he spotted his master climbing into a Vamp for a take-off and decided to gallop out for a “‘hello’’ bark. By the time he got there, however, the plane was under way. “Sub” ran smack into the business end of the jet and got himself a scorched crew-cut before he could get out so much as a single astonished yip. He is no longer air-minded.

410 Squadron

Graduates of the O.T.U. do not have far to go to find an operational fighter squadron. Canada’s first Regular Air Force interceptor squadron, No. 410, is being quartered at St. Hubert until its permanent base is ready. Another squadron, No. 421 is soon to be formed, and its ex-fighter pilot members are now being converted to Vampires at the O.T.U.

Commander of 410 Squadron is Sqn. Ldr. “Bob” Kipp, D.S.0., D.F.C., who was the first RCAF fighter pilot to destroy four enemy aircraft in one night. Sqn. Ldr. Kipp’s squadron, although manned by experienced pilots, is engaged in a never-ending programme of improvement and perfection. Under the functional control of Air Defence Group at Ottawa, the fighter squadrons are being pumped full of every scrap of information obtainable regarding interceptor operations. Working in conjunction with ground radar nets, they are designed to give the Air Force the nucleus of a permanent interceptor force.

As St. Hubert operates under a central maintenance system, the fighter squadrons receive the same servicing and repair work as does the O.T.U. Sqn. Ldr. Kipp heartily endorses Wing Cdr. Malloy’s praise of the ground crew and is planning to abduct a few of them when his squadron moves to its permanent home.

Auxiliary Squadrons

In order to provide a first-line supplement to the RCAF (Regular), 401 and 438 Auxiliary Fighter Squadrons, in conjunction with others across Canada, were reactivated at St. Hubert during the latter part of 1946. The auxiliary members were recruited from the vast reserve of RCAF veterans in the Montreal area and from civilians interested in non-permanent military activities.

The progress of these two squadrons since their reorganization is no less amazing than that of the permanent units at St. Hubert. Starting with little else than a few Harvards, a barren headquarters in Montreal and a skeleton membership, the two squadrons have moulded themselves into crack operational units.

Under the guidance of an RCAF (Regular) support party headed by ex-fighter pilot and leading jet pilot, Sqn. Ldr. “Stocky” Edwards, D.F.C., D.F.M., the Montreal auxiliary squadrons carry out their week-end programme of interceptor training at St. Hubert. Because of the large strength of each unit, the squadrons alternate their flying week-ends. Periodically, they participate in mock combat operations, the most elaborate of which have been “Operation Lakehead,” an attack on Hamilton’s industry by 401 Sqn., and ‘’Operation Quebec” by 438 Sqn. against the Canadian army.

It is difficult and perhaps unfair to give credit to any one person for a success which requires the contribution of all. Yet to a man, 401 City of Westmount Auxiliary Squadron agrees that much of their fine reputation and accomplishments is due to the energy, encouragement and devotion of their commander, Wing Cdr. J. W. Reid, D.F.C. He, in turn, credits squadron efficiency to his “one-man orderly room,” Sgt. R. Wilson, of Durham, Ontario. Sgt. Wilson, who has been an administrative helmsman on operational and training units since before 1942, is the pivot man for all squadron functions. In addition to routine administrative duties, he is circulation manager for the hundreds of news letters and bulletins that are mailed to auxiliary members every week.

Radar and Communications Squadron

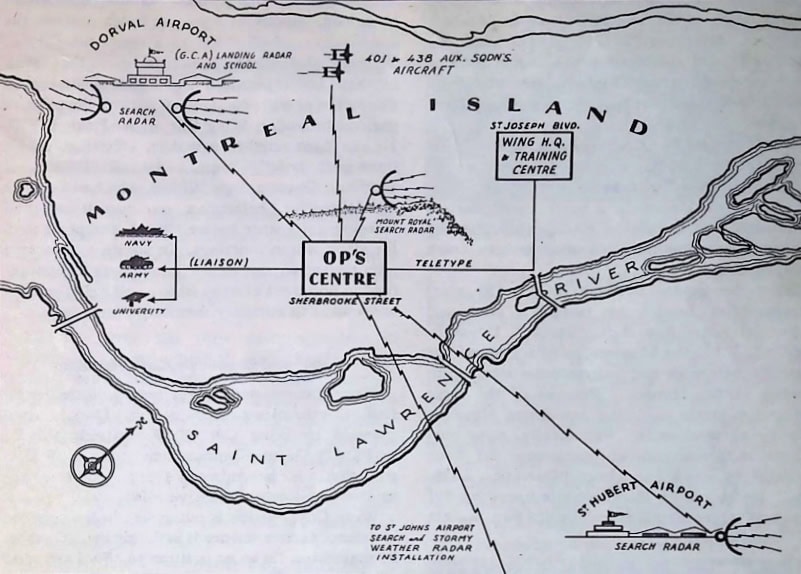

Newest component of the station is the Radar and Communications Squadron (Aux.), commanded by Wing Cdr. K. R. Patrick, O.B.E., ex-RCAF Group Captain and now an R.C.A. engineer, who has infected every member of the unit with his own aggressive spirit.

Wing Cdr. Patrick is outspoken in his opinions of defence tactics and needs in the air age. “Canada, he maintains, ‘‘is in no position to afford any kind of defence other than the most effective and efficient in the world . . . Our defence dollar must buy a dollar’s worth of defence, not ninety cents’ worth of tradition.” He believes that the basis of our defence programme must be a radar defence screen around our key cities. The Air Force agrees with him. The R&C Squadron is the result.

The squadron trains auxiliary personnel as communication technicians and operators, radar technicians and operators, signals officers, and radar controllers. Members receive three evening lectures per week from key. civilian research men and scientists in the electronics industry in Montreal, who may or may not have been affiliated formerly with the RCAF.

Operating the communications net and radar screen for the Montreal auxiliary squadrons, the R&C Squadron works in close conjunction with the auxiliary commanders but is detached from them, Sub-units of the R&C Squadron are operated at the University of Montreal, Dawson’s College at St. Jean, and St. Anne de Bellevue. Soon they hope to extend the coverage by deploying their units still further afield.

Assisted by Regular RCAF officers Fit. Lt. “Rudy” Rocheleau, D.F.C., and F/O R. E. Patterson, Wing Cdr. Patrick is building up an organization that promises to be a model for similar projects in other Canadian cities.

438 Auxiliary Squadron, commanded by ex-fighter pilot Wing Cdr. Claude Hebert, D.F.C., perpetuates the now famous record of the Alouette squadron. Maintaining its wartime tradition, the squadron is composed largely of French-speaking personnel.

The Alouettes, like their sister squadron in Westmount, have provided their headquarters with all the facilities and conveniences of a modern Air Force station. From welding shop to airmen’s lounge, the squadron exemplifies the zeal of those who are making the RCAF auxiliary programme the success that it is. Contributing to the momentum of 438 squadron is F/O F. N. Thompson, a recent immigrant to Canada from the RAF, who organized and now directs the auxiliary armament and photographic sections.

An important aspect of auxiliary activities, in addition to the attractions of flying and practical trade training, is the camaraderie which is so prevalent in our Service. The various institutes provided by the squadron for the convenience of all ranks make for a fellowship to which all subscribe. Veterans who join the squadrons find the canteens more comfortable and attractive than they had known before, and the recruit discovers a club whose. like might ordinarily have been beyond his means.

The Inner Sanctum

The Station Headquarters, from which control of the complex structure of St. Hubert is exercised, is directed by Wing Cdr. Baxter Richer, D.F.C. His association with the station began in 1941, when he was the Chief Flying Instructor of the S.F.T.S. In 1944, after two years with Bomber Command in U.K., and again in 1947 after attending the RCAF Staff College, he was appointed to St. Hubert as Commanding Officer.

Trustee of station housekeeping is Sqn. Ldr. Cail Vinnicombe, the C.Ad.O. With his faithful mascot, “Spike,” a brindle boxer, and a fire-engine-red MG, he tours the station, checking for the inevitable loose ends that arise in day-to-day administration.

The Station Warrant officer, F/Sgt. J. J. A. St. Laurent, divides his time between routine disciplinary duties and the difficult task of keeping the P.T. and recreation programme abreast of the rapid expansion of the station. The airmen are unanimously in favour of any steps which will improve extra-curricular facilities. Typically enthusiastic in this respect is fire-fighter LAC “Pete” Lemay, ex-member of Ottawa’s renowned “Dollard” Air Cadet Sqdn., who vigourously champions such distinctive innovations as intersection six-man football and the introduction of fencing into Service P.T.

Conclusion

RCAF Station St. Hubert, despite its tremendous achievements in the short space of three years, is nevertheless only in an embryo phase. The emphasis on interceptor defence will continue to grow, and St. Hubert will undoubtedly grow with it.

Meanwhile, as a design for the future, the record of this station speaks for itself.