The North-West Staging Route

Part 2/7

(reprinted from the March 1957 issue of The Roundel)

By Flying Officer S.G. French

(Part One brought the writer by train from Ottawa to Edmonton. So far he has traced for us the origins of the Route, shared a chance post-prandial with the uncle of “Wop” May, showed himself to the gibbons in the Calgary zoo, related a few episodes from the early days of bush-flying in the North-West, and wrestled with parachute-harnesses while waiting for the sked-run to forward him from Namao to Whitehorse—Editor.)

Our aircraft was loaded with airmen, civilians, and supplies, all bound for various northern outposts. As it droned its way over the five hundred or so miles of more or less settled country that lie between Edmonton and Fort Nelson, where we were to stop for lunch, I could not help reflecting again how much the northernmost reaches of the land below me owed to those venturesome bush-pilots of not so many years ago. I have already referred to the work of a few of them, and this seems as good a place as any to mention two or three more examples of the sort of activities in which they were engaged.

In April 1924, “Punch” Dickens was one of the handful of officers who had been granted permanent commissions in the R.C.A.F. when the Service was officially authorized on the first of that month. Later in the year he wrote a significant report on the value of aircraft for travel in the wilderness. In 1929, after he had left the Air Force, he made a successful experiment in the delivery of airmail when, in his Fokker Super-Universal, he flew from Edmonton to Fort Smith, Fort Resolution, Hay River, Fort Simpson, and finally back to Edmonton. Also in 1929, flying for Western Canada Airways, he landed his ’plane at Aklavik in order to pick up a load of furs. The airlifting of that one load netted $40,000 more profit on the furs than would have been made had they been brought out, in the usual way, by boat.

The same year marked another notable contribution to the aerial development of Canada. In August, Leigh Brintnell flew a prospector named Gilbert LaBine from Winnipeg to The Pas, Fort McMurray, down the Mackenzie to Fort Simpson and Fort Norman, then up the Bear River and around the southern shore of Great Bear Lake. While flying around the lake, LaBine noticed spotted streaks of orange along the shore. The following summer he returned by air to stake claims and take samples. Subsequent tests revealed that he had discovered the world’s richest lode of pitchblende, the ore of radium.

Three years later Brintnell took up the supplies for Great Bear Lake’s first picnic — eighty cases of liquor (for 500 men). There was high revelry, and many were the games of strength and skill that livened the proceedings; but, to quote Brintnell’s own words, “there was not one unkind word spoken, or one fight.”

We had eaten lunch at Fort Nelson, and the C-119 was headed for Whitehorse. Even from 9500 feet TI could get some idea of the grandeur of the North. Every once in a while our track would cross the Alaska Highway, a long, seemingly never-ending break in the terrain. It looked rather like a silver string tossed from an aircraft, and I was able later to appreciate the sentiments of the anonymous poet whose words grace the walls of several restaurants along the Highway:

“Winding in and winding out

Leaves my mind in serious doubt

As to whether the loute

who built this route

Was going to hell or coming out.”

We flew over an infinite number of rushing rivers and bejewelled lakes. The glacier-covered mountains .were becoming more and more frequent, each one like the tear-stained face of an old Indian squaw. The North is rich in natural landing-fields, and the abundance of its lakes and rivers makes it ideal for pontoons in the summer and skis in the winter.

When we landed at R.C.A.F. Station Whitehorse I was met by Flying Officer Cairncross, the station’s Ground Defence Officer, general all-round handyman, and acting Public Relations (and general information) Officer. He showed me to my quarters and orientated me in relation to the station, its personnel, and the city of Whitehorse. I paid my devoirs, dined well and not too unwisely, and set out for Whitehorse with a light step and a pioneering spirit.

There are few people, even in this generation, whose imaginations have not at some time been stirred by stories of the Yukon and the trail of 98. In August 1896, George Washington Carmack and two Indians, Skookum Jim (to whom credit is given for the actual discovery) and Tagish Charlie, found large deposits of placer gold on Bonanza Creek, a tributary of the Klondike River. News of the strike swiftly led to the Klondike gold-rush, which in turn led to the rapid growth and development of the Yukon Territory and Whitehorse — and, of course, to the poems of Robert W. Service. Thousands of men and women came from every corner of the world to join the rush, which rivalled that of California back in ’49.

The airfield at Whitehorse sits on a plateau which overlooks the city from an impressive height. One can either walk down a very precipitous sand-cliff, or one can take a two-dollar taxi-ride along the Alaska Highway, which has a cutoff to Whitehorse. I did the latter. My first call was on the ‘“Whitehorse Star”, the local weekly newspaper. Its editor and owner, bearded Mr. Harry Boyle and his beautiful Chinese wife, met me in his office and outlined some of the possibilities open to me in Whitehorse. Mr. Boyle then assigned one of his small staff, Mrs. Furber, as my guide and mentor in the city.

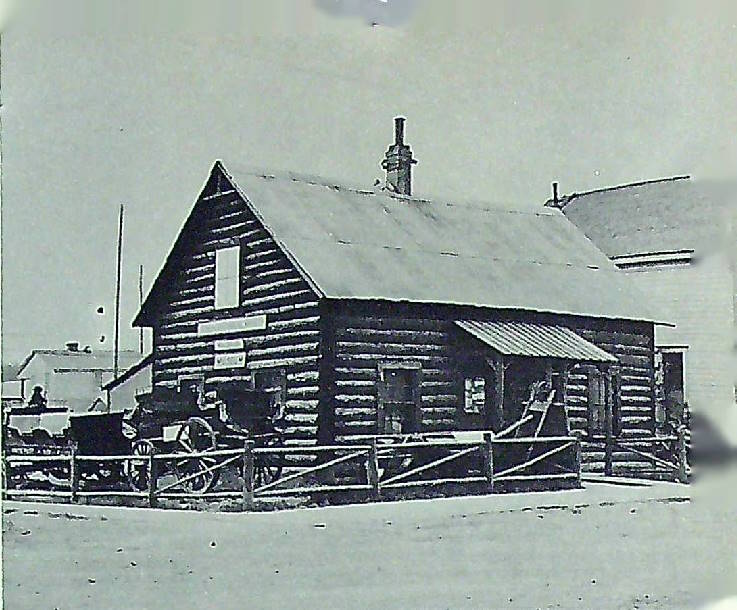

Mrs. Furber proved to be as knowledgeable as she was charming. The first person that she took me to see was Mr. W. D. MacBride,1 of the White Pass and Yukon Railway. Mr. MacBride is an old gentleman who has spent most of his life in the Yukon and who has devoted a vast amount of his time and money to the preservation of its past. He founded MacBride’s Whitehorse Museum. He not only established it, he even bought the building and paid out of his own pocket for almost all the exhibits. The latter include items ranging in variety from an ancient Indian war-hatchet and three unpublished poems by Robert Service, written while he worked in the Whitehorse Bank of Commerce, to the first sleigh used on the northern Royal Mail run.

In his office at the depot, Mr. MacBride keeps an immense Scrapbook, the size of a large desk-top. It is divided into sections, each one of which deals with one aspect of northern life. The book contains photographs, personal entries made by its curator, and newspaper clippings many of which are yellow and brittle with age. Mr. MacBride has a tremendous feeling for the past, a deep realization — somewhat rare today — of the importance of preserving records for posterity of the contemporary and the comparatively recent past. It will probably be several decades before Canada as a whole fully appreciates what he has done.

Mrs. Furber, in introducing me to him, mentioned that I was writing an article for “The Roundel”, the official publication of the R.C.A.F.

“How do you do, son,” said Mr. MacBride. “I hope that you’re not another of those ignorant writers from ‘outside’ who come up here from the big magazines or to write a book and then go back and tell a bunch of lies about us.”

I liked him immediately — and I trust that I have kept his not-too-subtle warning in mind! “Outside” is the word used by northerners to designate the entire world which lies outside the North, and it is always uttered in a rather compassionate tone. Not once did I meet anyone who was sorry to be “inside”.

As we sat talking, I happened to glance out of the window. All of a sudden the Yukon River, with its old retired stern-wheelers, was hidden by what appeared to be a miniature train. Engine, coaches, and freight cars, all looked like scale-models of real rolling-stock. Mr. MacBride told me a little of the history of this railroad.

“Construction was begun”, he said, “in the spring of 1898. Men, horses, and material were landed at Skagway, in the Alaska Panhandle, on tidewater of the Pacific Ocean. From sea level at Skagway, this narrow-gauge railroad — it’s 36 inches — gradually was built to a summit of 2,885 feet in the first twenty-one miles. Its highest evolution was reached at Log Cabin, B.C., Mile-Post 33, at an altitude of 2,916 feet. The building of the railroad was attended by more than ordinary difficulties. The terrain was not only scenic, it was treacherous. It was a thousand miles from supply bases. There were no telegraph lines. There were no bulldozers or similar equipment. The building of the road was accomplished with axes, picks and shovels, horses, wheel and hand scrapers, and dynamite.

“Thirty-five thousand men worked on the road, all told. Most of them were anxious to reach the gold-fields, but they were working either because they didn’t care to start down-river until the opening of navigation, or because they required capital to furnish a grubstake for prospecting. On August 8th, 1898, fifteen hundred employees hoisted their picks and shovels on to their shoulders and departed on a gold-stampede to Atlin, B.C. It was necessary to replace not only the workers, but the picks and shovels as well.

“The line to Whitehorse was completed in June 1900. During its construction, a winter horse-drawn freight service, known as the ‘Red Line Transportation Company’, was operated from the various railheads to Carcross over the ice of Lake Bennett.”

Mr. MacBride then showed me the legend printed on the back of a pass which was issued to one Arthur Copeland in the winter of 1899, for a trip on the Red Line from Bennett to Carcross. It bore the signature of M. J. Heney, builder of the White Pass Railway. Here is a copy of it:

CONDITIONS

This pass is not transferable, and must be signed in ink or blood by the undersigned person, who, thereby accepting and using it, assumes all risks of damage to person and baggage. The holder must be ready to “mush” behind at the crack of the driver’s whip. “Dewar’s Crown Scotch” and “Concha De Ragelias”, carried as side-arms, are subject to inspection, and may be tested by the officials of the road or their duly authorized representatives.

Passengers falling into the mud must first find themselves, and then remove the soil from their garments, as the Red Line Transportation Company does not own the country and the authorities are not giving it to cheechakos.

No passenger is allowed to make any remarks if the horses climb a tree, and each one must retain his seat if the sled drops through the ice, until the bottom of the lake is reached, when all are expected to get out and walk ashore.

The holder hereof may gaze upon the mountain scenery, or may absorb the Italian summer, and, if specially desirous, may be permitted to watch the gleaming Northern Lights. If the passenger has but one lung, he will have permission to inhale the fresh air to capacity of said lung, but no more will be allowed.

I accept the above conditions. (sgd.) ____________________________

Although the sun was still high in the sky, it was supper time, and Mr. MacBride was hungry. I told him that I hoped to see him on my way through Whitehorse after my little trip up north, and Mrs. Furber led me to the Whitehorse Inn. There, at the table next to us, sat a middle-aged, jovial-looking man who evidently enjoyed life thoroughly. I was told that his name was T. C. Richards, that he owned the Whitehorse Inn, and that he was a millionaire. The story goes, apparently, that he won the Inn on the roll of a pair of dice, back in the old wide-open days.

As the evening progressed, many people joined us at our table, some of them to stay, some to drift on to other tables and other diversions. Who most of them were, I don’t know. Among them, however, were several, both men and women, who were — as one of our group expressed it — “just escaping from the pseudo-civilization outside.” Older men joined us, too, men who had come in the gold-rush days, men who had made fortunes only to lose them again.

Two such old-timers who joined us were Ollie Erikson and Stampede John, and the stories flew fast and furious. The waitress who brought us our overproof rum was a New Zealand girl who was hitch-hiking her way round the world.

The sun had dropped below the horizon at midnight. An hour and a half later, as I was climbing the hill toward the station, it was just beginning to reappear. The night air was invigorating, and already I found myself falling in love with this country and its people. Now, however, my need was sleep; for we were to leave for Aishihik early in the morning.

When I awoke, it was raining. After a hurried breakfast, I threw my flight bag into the trunk of the waiting car and climbed in beside the driver, L. A. C. Russ Skene. Then, after we had picked up Corporal “Shorty” Orr, the photographer, we drove off along the Alaska Highway. Through a country of mountains and glaciers we drove, past the junction of the Mayo Road (255 miles to Mayo and 353 to Dawson City), past Mendenhall Creek, past Champagne, where several Indians were attempting to re-civilize a few horses who had forgotten the feel of the saddle during the winter months which they had been allowed to spend ranging free in the mountains. As we twisted and turned, I spotted three moose in a little lake down in a valley beside the road. The sight delighted me, and my pleasure lasted until we passed that spot on the return trip, when I saw that my three moose were standing in exactly the same place and in exactly the same postures. They were, of course, stumps.

The cut-off from the Highway to Aishihik is just past a small settlement with the fascinating name of Crack-R-Crik, but we had to continue a little further, to Canyon Creek, in order to ’phone the Aishihik control-tower and tell them that we were about to start down the station road. We were warned to drive carefully, as the road might be slippery, and we were also instructed to call again from the roadside ‘phone about 20 miles in. I was very shortly to discover the reasons for such precautions.

We drove back to the cut-off and turned on to a single-lane dirt road. At the corner there were signs, one on each side, pointing to “R.C.A.F. Detachment Aishihik”. The one on the left read “84 miles”, the one on the right “72 miles”; but, although there seemed to be some doubt as to how far we would have to travel before lunch, there was no doubt that we could not turn back, for the forest through which this narrow route had been hacked grew right up to its edges.

All went well at first. The road was relatively flat, although the gumbo, made slippery by the rain, did not contribute to our mental comfort. Soon, however, we began to gain altitude; and, five miles from the Highway, at the foot of a grade aptly called “the 16%”, the car refused to climb any further through the mud. The road at this point, as at most of the other steep inclines, had been cut out of the side of the mountain, and when I looked out of the window beside me, I stared straight down into the valley below. If I had opened the door and got out, I would have had to take a remarkably long step.

As often as the driver backed up and took a run at the slope, the car slid on the mud, which was as slippery as ice, and several times I could have sworn that my side of the car was hanging over the abyss. Cpl. Orr and I decided that, if we wanted to have dinner by suppertime, we had better get out and push. “Shorty”, as his nickname implies, is as short as I am tall. We must have presented quite a spectacle as we strained and heaved at the back of the car, pushing ourselves ankle-deep down into the mud, our uniforms saturated by the rain and spattered by the skidding wheels. We finally reached the top after pushing for a distance of what the speedometer told us was four miles, but which we were subsequently informed was only two.

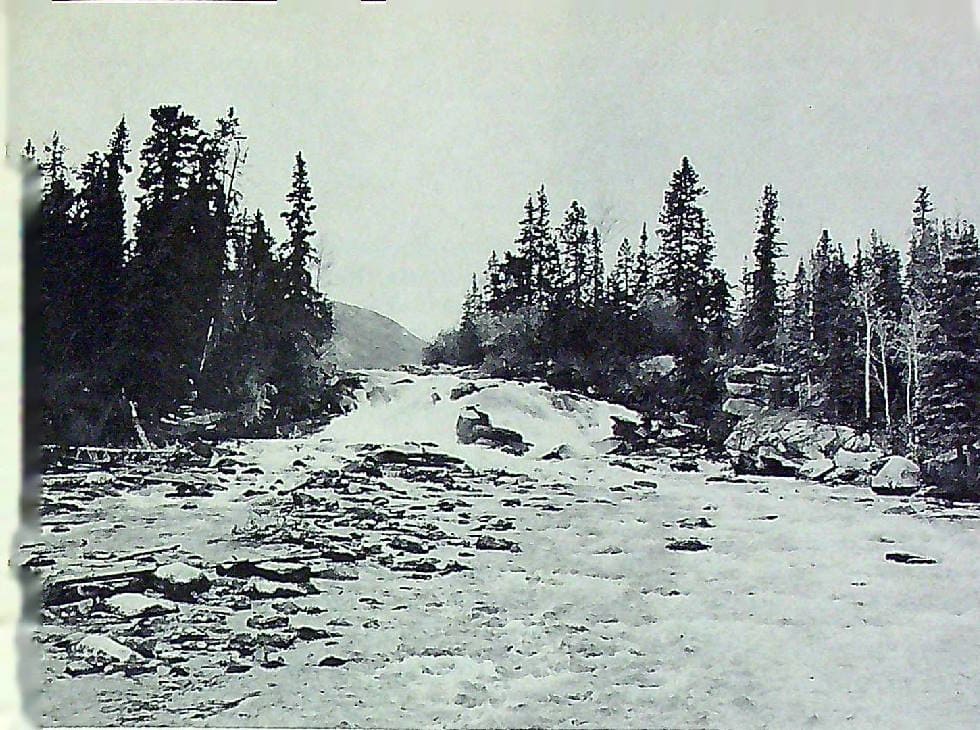

The remainder of the journey was very pleasant. At the 20-mile post, we once again phoned the tower. Fearing an accident because we had taken so long, they had already sent a power-truck out to search for us. If met us five miles further on at a beautiful little spot called Otter Falls. If the reader will take out his wallet and examine any of the five-dollar bills that he may find there, he too will be able to see Otter Falls. If he is a fisherman and prepared to travel far afield for his sport, he can stand upon that jutting rock to the right centre of the bill and haul in rainbow trout as fast as he can put his line in the water. Fish, I might add, are far from the only type of game in which that lovely country abounds. On the way in to Aishihik I saw a soaring black hawk with a wing-spread of some six to eight feet, a score of different kinds of ducks, beaver, several herds of moose, a grizzly bear with three cubs, and a large bald-headed eagle perched on the top of a tall pine.

Not long after I saw the eagle, our little cavalcade reached its destination and came to a halt amid the red log buildings of R.C.A.F. Detachment Aishihik.

*

Story from:

- A two-part article by Mr. MacBride, “The Trails of ’98”, appeared in the March and April issues of “The Roundel” in 1950. ↩︎