(reprinted from the 23 March 1956 issue of The Voxair)

PART III

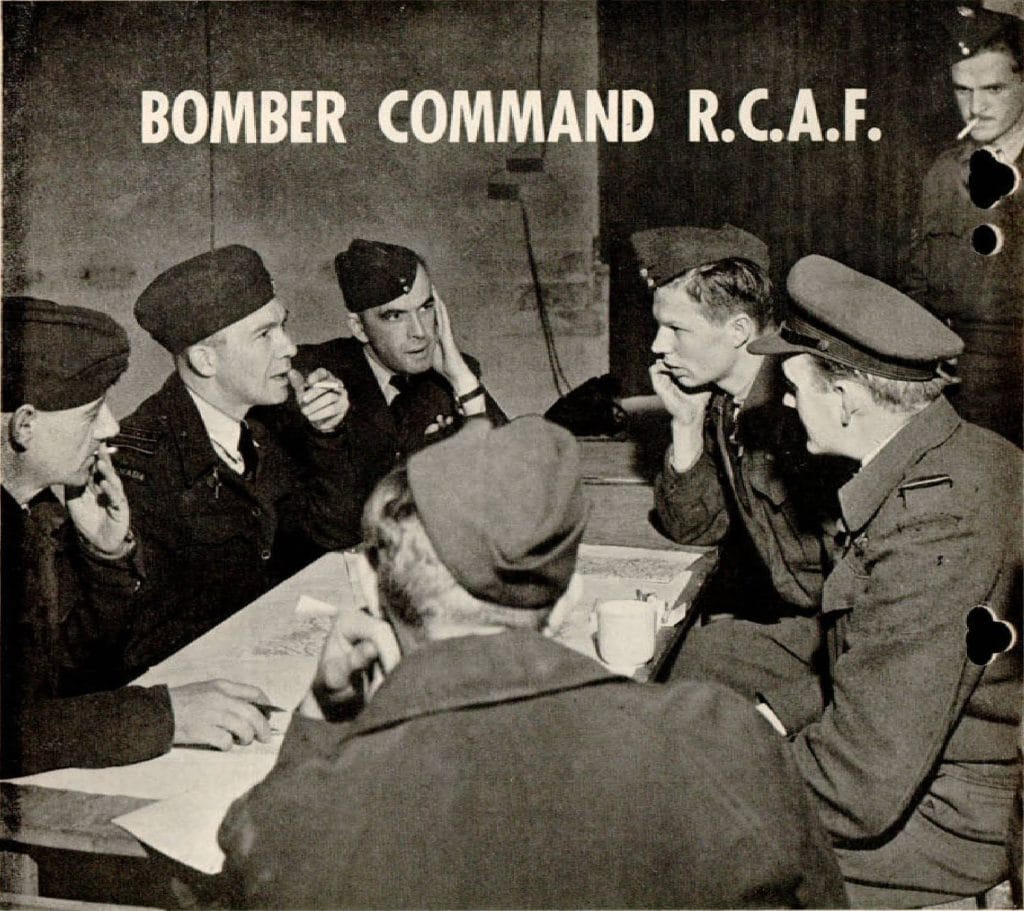

Parts I and II of this story dealt with the crew briefing, preparations for departure. and take-off on a bombing trip over Europe. In this concluding article the author tells of the activity over the target and the return to base.

We are now climbing as rapidly as possible—already the German radar screen has picked us up and is vectoring enemy night fighters in our direction. We must be at operating height before they contact us. Our next turning point is Sedan, France, and to reach it on time our navigators have had to make course alterations because of variant wind speed and directions. Navigational “fixes” are taken every few minutes by radar and dead-reckoning. Our course is designed to keep us clear of towns and known enemy ack-ack batteries. To stray a few miles means trouble. The bomb aimer is tossing his bundies of “window” through a port in the glass nose at regular intervals.

Near Aachen we have reached 18,000 feet and level off to maintain a steady cruising speed. There we encounter our first enemy activity. We must run through the search-light belt surrounding the Rhur Valley cities. Heavy flack is spasmodic but the radar-operated batteries are picking away at the stragglers. The enemy night fighters have finally contacted us—the first to do so drop parachute flares which attract others to the bomber stream.

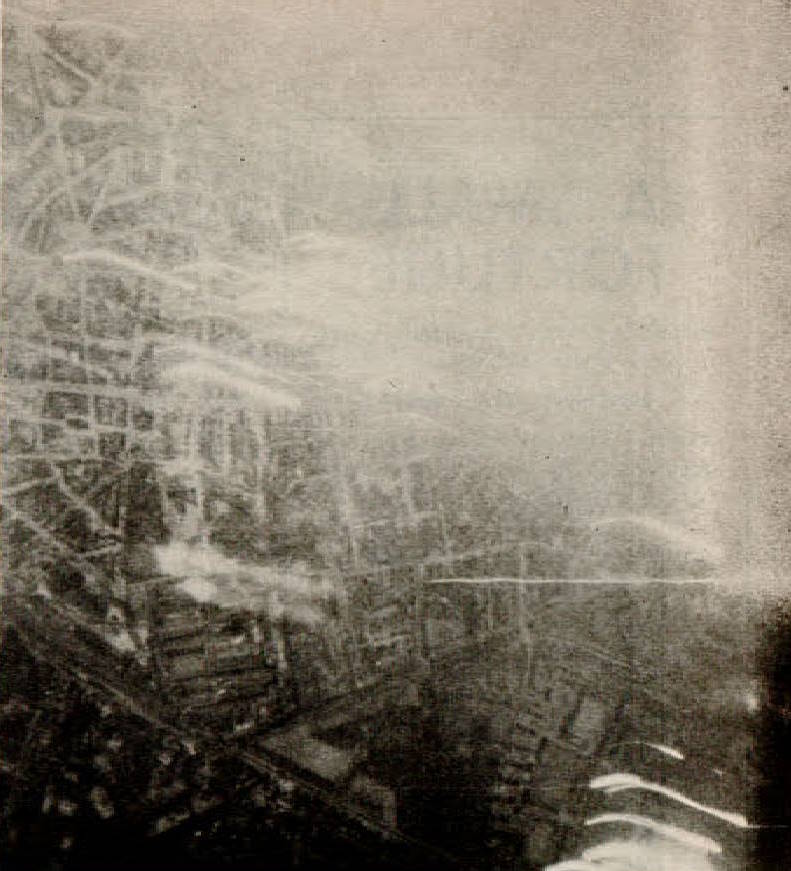

We reach a point 5 miles north of Cologne at 2016.3 hours, which means we are 0.7 minutes early, but since a few minutes are much more easily lost than gained we do not waste the excess time. It may be handy later on. Cologne itself is covered with an umbrella of bursting flak and is a very obvious landmark at this point. Our course now is designed to carry us to a point 60 miles west of Berlin and 50 miles north of the target Dessau. Enemy activity has increased considerably—there is no cloud cover and the night fighters have good visibility. Bombers caught by flak or fighters become torches that light up a huge area. Aircraft shot down are logged and a note made of their positions in the navigator’s log. By now the only crew members not keeping a lookout for danger are the navigators under their blackout curtain. At 2040 hours we alter course to by-pass a heavy flak battery and in doing so lose the extra time we had in hand. All towns along our route are throwing all they have in our direction it seems. Occasionally a “scarecrow” bursts

in the sky—a heavy shell designed to look like an exploding aircraft. Some of them aren’t scarecrows. We by-pass Braunshweig (Brunswick) with its searchlights and flak and reach our turning point north of the target at 2140 hours. We now alter course to due south. This course alteration confuses the night fighters who until now had concluded we were aimed at Berlin. The navigators now give the wind speed and direction and aircraft height and speed to the bomb aimer who feeds this information into the bombsight computer box. The bombsight is now ready for use. A few minutes before the first bombs are due to be dropped the Pathfinder crews drop their flares upon the aiming point —these are now visible in front of us. Fifteen miles short of the target the bomb doors are opened and the bomb aimer directs the pilot to the target. The navigators are now using a ground position indicator to aid in directing the pilot (this is an arrow indicating the aircraft position transposed by light on to a target area map). Conversation between the bomb aimer and pilot goes something like this — “left, left, steady,” (pilot alters course left) “right, steady, steady, steady.” (A very small alteration right.} “Steady, steady, steady.” (aircraft is coming up correctly on to the target).

The master bomber circles the target area with his deputy giving instructions over his radio transmitter. All bomber aircraft listen on his frequency and follow his instructions. If a red flare or flares have been dropped to mark the aiming point the master bomber calls for bombs to be dropped on the flare. If the flare is slightly off the aiming point he will ask for bombs to be dropped in such a manner as to be accurate. That is, he might instruct the bomb aimers to make an overshoot or undershoot or to aim to port or starboard of the flare. At regular intervals other Pathfinder aircraft drop new flares to reveal the aiming point.

When the bombsight cross-hairs and target coincide, the release button is pressed and with “bombs going—bombs gone” the Lancaster leaps upward as the heavy load leaves the bomb bay.

We must stay straight and level for another thirty seconds — the longest thirty seconds in a lifetime. As the bombs were dropped a flare was released automatically from a flare tube in the rear of the aircraft. This explodes in thirty seconds illuminating the country below. At this instant a camera installed in the bottom of the aircraft opens its shutter and takes a picture of the target. In this way bombing accuracy can later be assessed. After the red cockpit light flashes, indicating that the camera has done its duty, we are free to take evasive action to throw off any fighters in the target area and to escape from the concentrated flak barrage.

The danger of being hit by falling bombs must be guarded against by a careful lookout above. The navigator gives the pilot his course to fly from the target and as quickly as possible we get out of the area of illumination provided by bombs, flak bursts and searchlights still in operation.

As we leave the target area on the first leg home a quick assessment of the calibre of the raid is made and logged.

We are now travelling at a higher speed because of the lack of the bomb load. Focke Wulf 190’s are active in the target area and we weave through the sky to throw them off. To avoid a direct attack the pilot executes a violent cork-screw-like motion with his aircraft and in the darkness usually eludes the pursuer. The danger lies in being caught unawares. The bomber carrying up to 1500 gallons of petrol makes a beautiful target. Long range twin-engined enemy fighters can follow the bomber stream all the way back to England and at no time must the constant vigil be relaxed. We are now flying toward the southern part of Germany to by-pass the Ruhr Valley. The return trip takes us past Nuremburg with its flak umbrella, between Mannheim and Stuttgart, each putting up flak and searchlights to warn us off. Flak is now becoming sporadic and night fighters are having to return to base to refuel. We pass Metz in France, then Rheims and turn northward to cross the French coast south of Boulogne. Some crews become careless after seven hours of flying and tension and the enemy night fighters are aware of that. Various ruses are used to distract a gunner’s attention. While one fighter feints on one side another closes in from the opposite side. Bombers have even been shot down over their own aerodromes when preparing to land.

Our return course carries us across the channel to Reading, west of London—the area of London and the Thames estuary being as dangerous to fly over as many German cities. Four years of German air raids have made the British gunners very touchy.

We reach our base in southern England almost simultaneously with the rest of our squadron. Pilots call the control tower, identify themselves and receive their landing instructions. Damaged aircraft or these with wounded on board receive priority. On landing we taxi to our dispersal point and turn the aircraft over to our ground crew who have been waiting. They as well as we, are glad to see the old kite parked in her place again.

The crew truck picks us up and returns us to the flight section. We turn in our chutes and Mae Wests and move on to the interrogation room. Here the padre greets us with coffee and rum.

The crew is interrogated as a whole by the intelligence officers — they want to know about bomb damage on the target, time of bombing, enemy activity, aircraft shot down, parachutes seen, and any other information which might be of use in further raids. Afterwards the navigation, bombing, and wireless sections are reported to. The Met. man wants to know what we thought of his predictions. We give him a report on weather over the continent. All that remains after the interrogation is another ops meal of bacon and eggs. By now another day is dawning and another group of crews await the signal from Bomber Command.

(Pictures courtesy of Director of Public Relations, R.C.A.F. and private collections.)