(reprinted from the 2 March 1956 issue of The Voxair)

PART II

Crew briefing completed the Lancasters take off and join the bomber stream. Shortly after crossing the coast of Europe they pass into enemy-held territory.

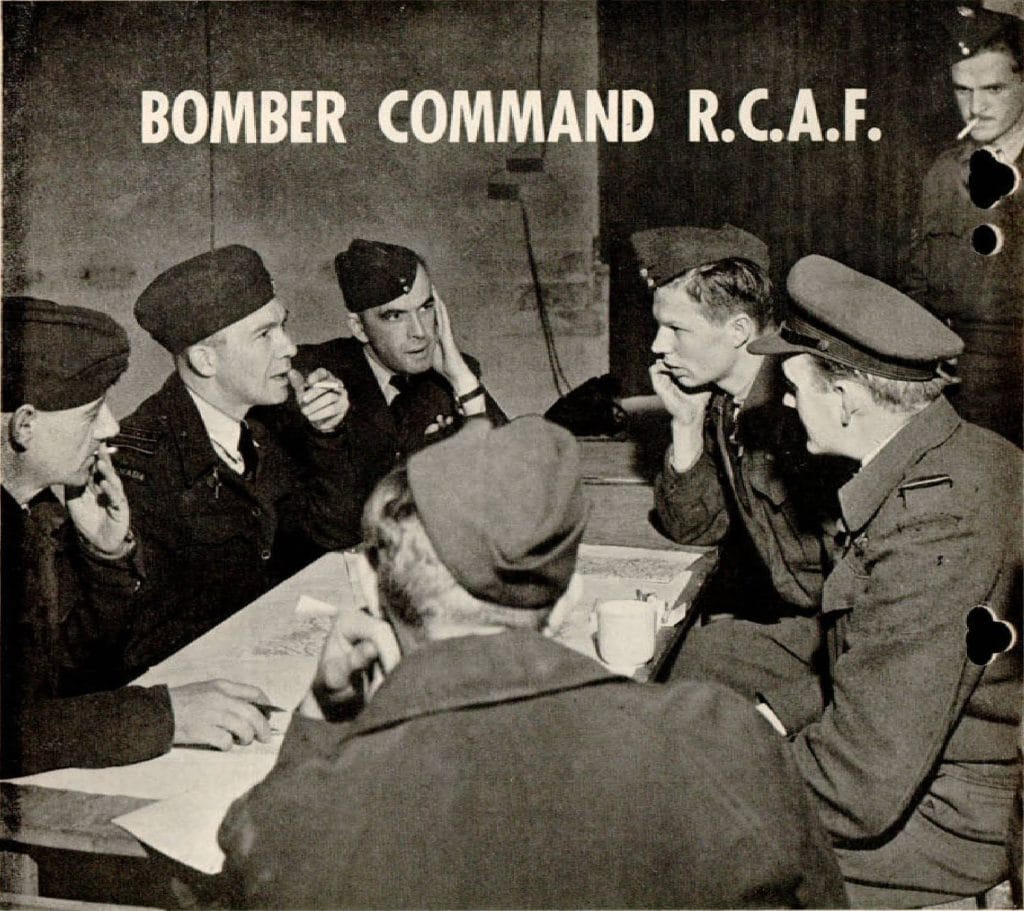

METEOROLOGICAL BRIEFING

The “Met” officer is the usual Englishman nicknamed Cloudy Joe — a somewhat controversial figure on the operational station. At times he has to withstand considerable ridicule and is blamed for the ather, much as the peacetime ather man. He tells the crews at might be expected in the way reather during the flight. e cross section is drawn on a ekboard showing clouds and cloud heights from base, across the channel, over Europe and at the target. With the use of a projector barometric pressure lines are super-imposed on a map of the continent. thus showing the positions of weather fronts that would have to be contended with during the trip. Icing conditions are discussed, cloud breaks are noted with their elevations so that crews may be able to make use of them, and wind velocities and directions considered. Just before an operation take-off, a Mosquito aircraft would report back from a “met sweep” over the proposed route as a check on the meteorological predictions.

NAVIGATION BRIEFING

Navigators and pilots are briefed ~al the track and turning points on various legs of the trip to and from the target. Each turning point is. to be reached at a specific time. Courses to be flown are calculated from the wind speed and directions predicted by “Met.” These of course will probably have to be changed later as wind variations are encountered en route. A rice paper flimsy containing essential navigation information is given each navigator. In the event of being shot down each navigator is expected to eat the flimsy to guard against information getting into enemy hands. All navigators and pilots synchronize watches at this time.

INTELLIGENCE BRIEFING

The senior intelligence officer discusses flak and searchlight concentrations. British intelligence could predict how many heavy, medium and light flak batteries could be expected at various towns en route. Crews are advised when to expect to encounter enemy fighters. Escape tactics in the event of being shot down are discussed.

BOMB AIMER’S BRIEFING

Bomb aimers are briefed separately on the details concerning the bombs being used, fuses, order in which bombs are to be dropped, and the setting up of the bomb-sight and its control panel. Large-scale pictures and photographs of the target are studied and memorized by the bomb aimers.

The bomb aimer’s duties, apart from the actual bomb drop itself, consist of watching for enemy aircraft and dropping “window.” Windowing is the release of metallic-covered strips of paper from the aircraft in bundles—one bundle every few minutes. This is done over enemy territory and is an aid in confusing the German radar screen. Each bundle opens up into a cluster of metallic strips, which give a “pip” on the German radar somewhat similar to that produced by an actual aircraft. This reduces the chances of an aircraft being singled out for flak treatment. When caught by radar-operated flak batteries, an aircraft could confuse the gunners by rapidly releasing a number of bundles of window.

WIRELESS OPERATOR’S BRIEFING

To prevent jamming by enemy radio the frequency used by Bomber Command is changed every few hours. These frequencies, plus those reserved for emergency use, as well as other secret data, are given to the wireless operator in a rice paper flimsy — to be disposed of in the same way as that of the navigator.

The briefing complete, crews go straight to their particular aircraft after first picking up parachutes and Mae Wests. Trucks carry the crews to the dispersal point. Last checks are made on aircraft equipment.

At this time the station padre and C.O. usually pay each aircraft a visit. The padre carries a supply of chewing gum, cigarettes and ‘‘wakey-wakey” pills for those who think they might need a stimulant. These latter are useful for gunners who may become overtired due to cramped positions and cold.

Ten minutes before take-off time crews take their positions in the aircraft. The intercom is checked with each man—pilot, engineer, bomb-aimer, navigators, wireless operator and two gunners. Engines are started and checked, radar equipment is also checked. Any unserviceability is indicated by releasing a red Very cartridge from the aircraft. This brings the ground crew service trucks to do last-minute repairs. If the aircraft is unserviceable, the crew takes over one of several spares always in readiness.

The aircraft, in this case Lancasters, are now taxiing around the outside perimeter track and approaching the down-wind end of the runway to be used. Individual aircraft move out of their dispersal points and into line for take-off positions. Since the trip will take approximately eight hours, the Lancasters are taking off in day-light but will be flying in darkness by the time they reach the French Coast.

On receiving a green light from the traffic control officer, the first Lancaster moves down the runway. Weighing up to thirty-three tons the aircraft gains speed slowly and after using up a mile of runway lifts into the air. This is the crucial moment of any take-off, even a momentary engine failure could cause trouble. As soon as the first Lancaster is clear of the runway the second in line takes off.

There is a complete radio silence maintained by both aircraft and aerodrome control tower—any transmission could be picked up by German listening posts. More than one raid ran into heavy going because of idle talk or disobedience of radio silence.

Once the aircraft is airborne and climbing, a thorough checkup is made once more on the engines, aircraft performance, bombsights and navigation equipment. As there is still time before setting course on the first leg, the Lancasters circle around the aerodrome vicinity climbing steadily. As the time for setting course arrives each passes over the aerodrome on course and on time. At a few thousand feet all crew members plug in their oxygen tubes, as a liberal supply of oxygen aids night vision and helps to keep the crew warm and awake.

The bombers from the various squadrons scattered about southern England fly on converging courses until the entire raiding group is flying on what is called the “stream.” As each plane has a different time to reach turning points, and eventually the target, the bomber stream stretches over many miles in length and two or three miles in width.

Our Lancaster “C” for Charlie has set course from the base at 1743 hours (5:43 p.m.). We have climbed to our altitude of 2,000 feet in a few minutes, and half an hour of flying over the now darkening countryside brings us into the ever-growing bomber stream. The aircraft fly along independently but yet in close proximity. Our first turning point is at Reading, west of London. We reach it at 1803 hours right on time and the navigator instructs our pilot to turn on a course calculated to carry us across the English coast at a predetermined position. We have now reached the English Channel. Any noticeable casualness in the crew disappears, the gunners fire a few practice rounds to make sure the Brownings are working properly and the crew settle down to the business in hand. Very little conversation is carried on. All that can be heard over the intercom is the occasional word between the navigator and pilot or between pilot and gunners, it has become dark except for the last red color behind us in the sky — no lights are shown anywhere. The navigators are hidden behind their blackout curtains and the pilot and engineer read the cockpit instruments by their luminosity. The gunners are carrying out a systematic search of the sky above and below—one must keep a lookout for friendly as well as unfriendly aircraft. The other aircraft have all but disappeared in the growing darkness as we cross the French coast south of Dieppe. In a few minutes we are over the battle area of the American, British and Canadian ground forces. Continued gun flashes are visible but little else. Before long we pass into enemy held territory.