by Major W.A. March

(Republished from the 2 March 1994 issue of The Voxair)

By the summer of 1943, preparations in England for the upcoming “Second Front” in Europe began to reach a fever pitch. New Canadian air force units were formed, or transferred overseas, to fill the requirements put forward by Allied commands as they geared up to provide air support to the planned invasion. More and more of these units were attached to the Second Tactical Air Force (2TAF) until by August 1943, approximately fifty per cent of this formation was composed of squadrons and personnel from the RCAF. Up until this time, Canadian medical support to the RCAF had consisted of medical officers assigned directly to their respective squadrons, however, the increase in the number of Canadian units belonging to 2TAF meant that a higher level of medical services would be appropriate. Therefore, on 16 August 1943, an Air Ministry Order was published which authorized the formation of No. 52 (R.C.A.F.) Mobile Field Hospital (MFH).

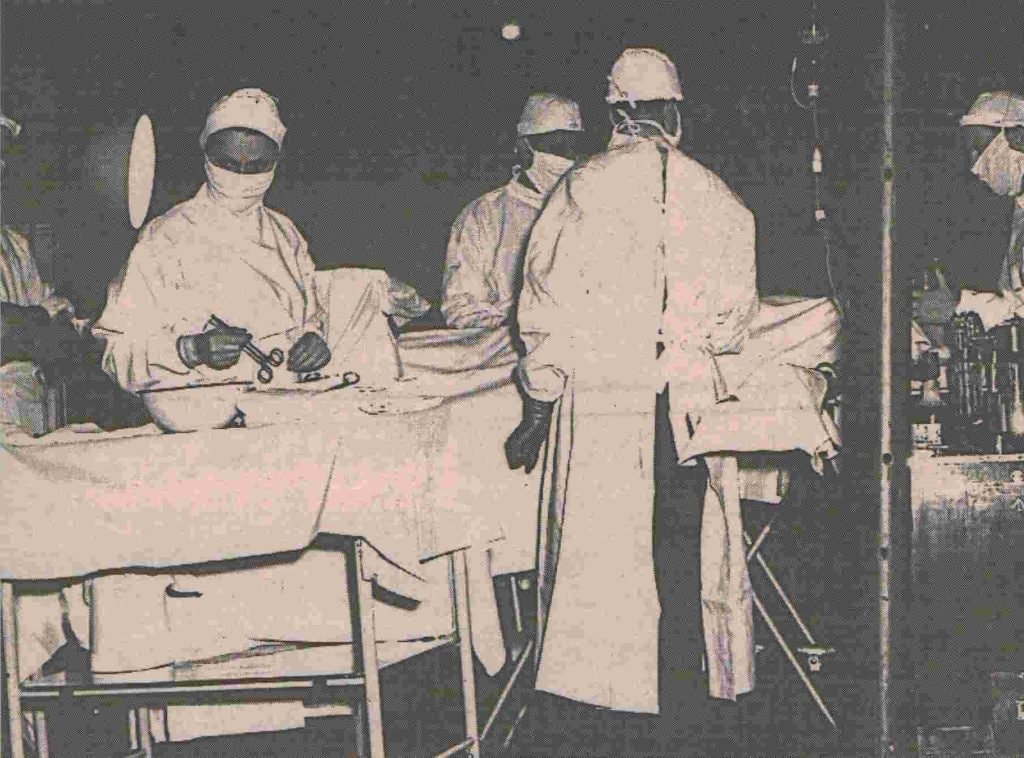

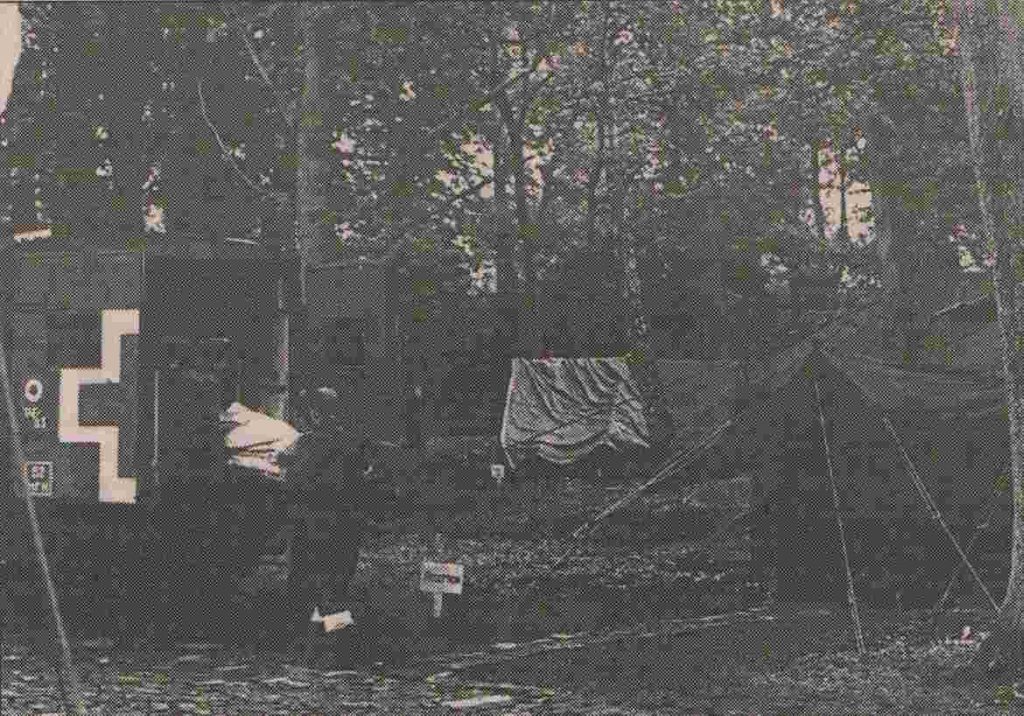

Formed at RAF Station Detling, Kent, No. 52 MFH was one of two mobile field hospitals attached to No. 83 Group of 2TAF and was to be the principal RCAF medical contribution to this organization. It was a totally self-contained, mobile unit, equipped with sufficient transport to carry all of its assigned equipment and patients. Totally under canvas, the hospital could be taken down, or set-up in a matter of hours as it followed close behind the combat units. The MFH would receive the sick and wounded, army as well as air force, from collecting zones and then treat the patients until they were fit to return to duty or transferred to more permanent medical facilities. It formed the first link in the evacuation chain and also provided specialist attention for aircrew when the need arose.

Throughout August 1943, staff began to trickle into the hospital. As the approved staff consisted of four medical officers, two nursing sisters, an administrative officer and approximately 70 other ranks, it took several months before they had all arrived for duty. During this period, under the direction of the Commanding Officer, Wing Commander, J.M. Growse, all available personnel undertook intensive training throughout southern England. Medical personnel undertook courses specializing in the types of casualties they could expect while non-medical staff underwent training on camp defence, small arms, gas and on how to avoid booby-traps. Everyone participated in practice moves until the hospital became proficient in convoy driving and procedures. Busy as they were there was still time to indulge in that favourite Canadian pastime overseas hockey.

Unfortunately, No. 52 MFH did not do well during its formative months and results such as a 9 to 1 defeat at the hands of 410 Squadron were not uncommon. The solution to this problem, even for a medical unit, was typically military as the hospital War Diary noted: “Team from this unit seemed in poor physical condition. Organized P.T., 1 hour daily for whole unit, initiated. Regular parades daily will be held in future.”

Finally, on 6 June 1944, all of their training paid off as the invasion was launched. On D plus 2 (8 June), the advance surgical team from the MFH landed at Bernieres-sur-Mer and immediately began to treat casualties. Located near an airfield, the surgical staff operated under harassing fire from German snipers and the occasional bombing. Eleven days later the remainder of the hospital landed on the beach at Courseilles-sur-Mer in the midst of a welcoming German air raid. Included with the main party were two RCAF Nursing Sisters whose arrival in Normandy was described in a Canadian Press news dispatch in the following manner: “Tin hats on, battledress trousers tucked into rubber boots, …Dorothy Mulholland of Georgetown, Ontario, and D.C. Pitkethly of Ottawa, walked down the ramp of an assault craft on to a Normandy beach this morning, the first Canadian service-women to land in France.” Soon these two nurses would be hard at work as the hospital became fully operational.

Over the next five months, the hospital moved a total of seven times as it followed the Allied armies across France and Holland. In the second week of October, the unit arrived at Eindhoven in Holland sharing winter quarters in an abandoned German naval hospital with a British MFH. A hospital routine was quickly established whichallowed the staff to incorporate an intensive welfare program for the patients which included a library, games and various clubs operating with “donated” equipment. The hospital routine was rudely shattered on 1 January 1945 when the Luftwaffe attacked the airfield at Eindhoven. By the end of the day over 40 casualties suffering from bullet wounds and burns had arrived at the hospital. There they were to remain for longer than normal because the German attack had destroyed many of the air evacuation aircraft. Two days later, things were back to normal and the seriously injured patients were flown to England.

The hospital moved three more times before the end of the war until it came to its final location in Germany at Luneburg, some 70 miles east of Bremen. The unit became non-operation on 8 August 1945 when it was ordered to return to Dunsfold, England, where it was disbanded. The only medical facility of its kind in the RCAF, the wartime record of the MFH was short but active. For the casualties, the sick, and the returning prisoners-of-war who passed through its canvas walls, No. 52 (R.C.A.F.) Mobile Field Hospital was a welcome piece of home so far away from Canada.